Please read the following and then return to complete your survey.

Introduction

Hi! Welcome to this chapter on Carpal Tunnel Surgery. We’re going to cover everything you need to know about carpal tunnel surgery. We’re going to cover relevant anatomy, history and examination, investigations and surgical technique as well as pre and post operative planning and a couple of tricks and tips along the way.

By the end of this course, you should be able to:

- Describe the anatomy of the median nerve in the hand and wrist

- Take a history for a patient presenting with carpal tunnel syndrome

- Examine a patient presenting with carpal tunnel syndrome

- List the relevant investigations for a patient with carpal tunnel syndrome

- Explain how to perform an open carpal tunnel release

- Explain the postoperative management of a patient who has undergone carpal tunnel surgery

Carpal tunnel syndrome is a common condition mainly in the middle aged and elderly population that is caused by compression of a nerve called the median nerve in the wrist, as it goes through a tunnel called the carpal tunnel.

Anatomy is the your map of the human body, so we’re going to start there so you don’t have to drive blind.

This whole web page should take you around 30 minutes to read, so keep scrolling until you finish the whole text.

TOPIC 1: ANATOMY

Bones of the hand and wrist

In this topic, we will cover anatomy of the hand and wrist, anatomy of the median nerve and anatomy of the carpal tunnel.

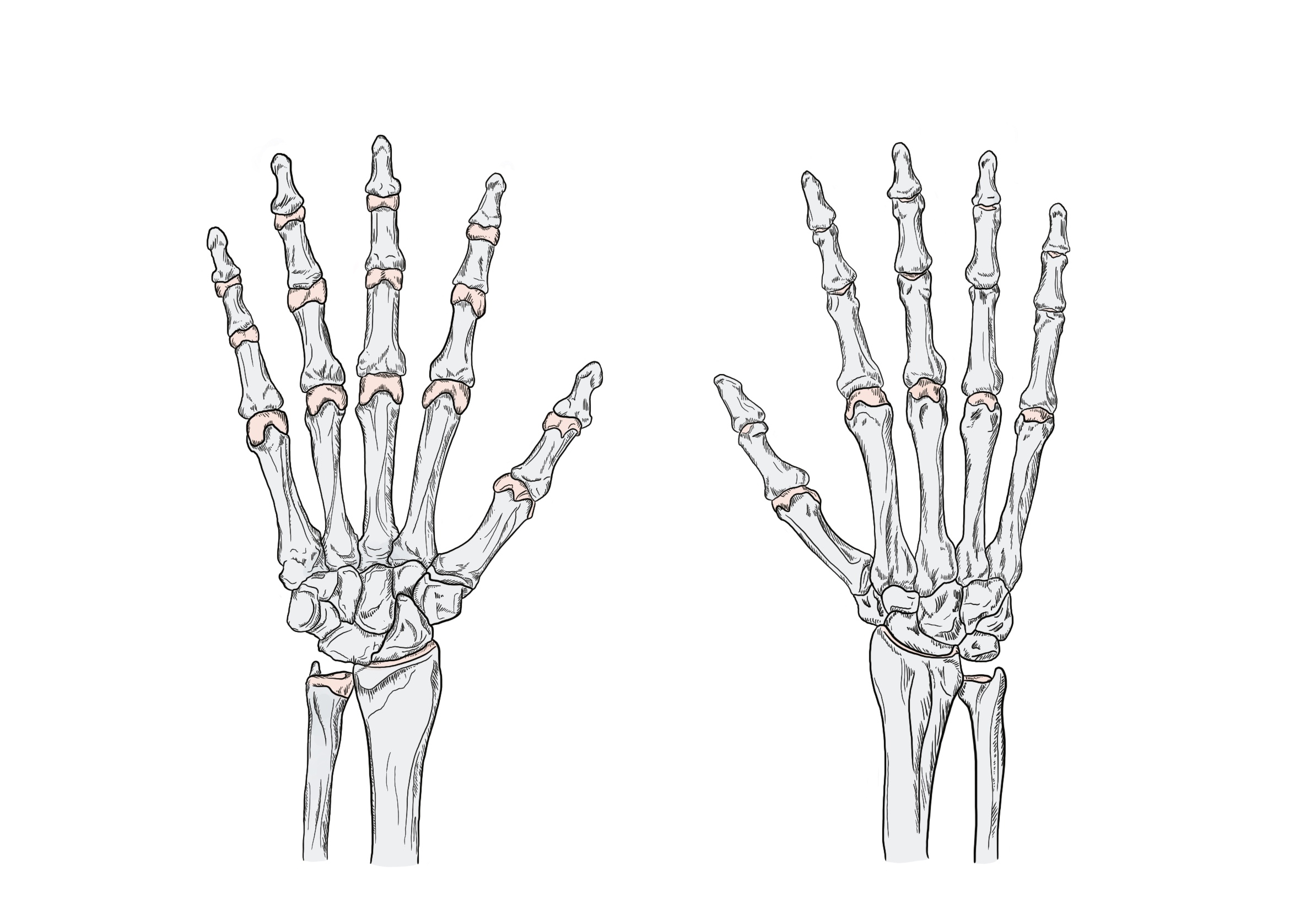

In Figure 1, you can see the bones of your fingers: distal phalanx, middle phalanx and proximal phalanx, and the bones of your hand: the metacarpals. The bones of your wrist are the carpal bones. Proximal to your wrist, you’ve got your radius on the thumb side, and your ulna on the little finger side. In the thumb you have a distal phalanx and a proximal phalanx only, There is no middle phalanx.

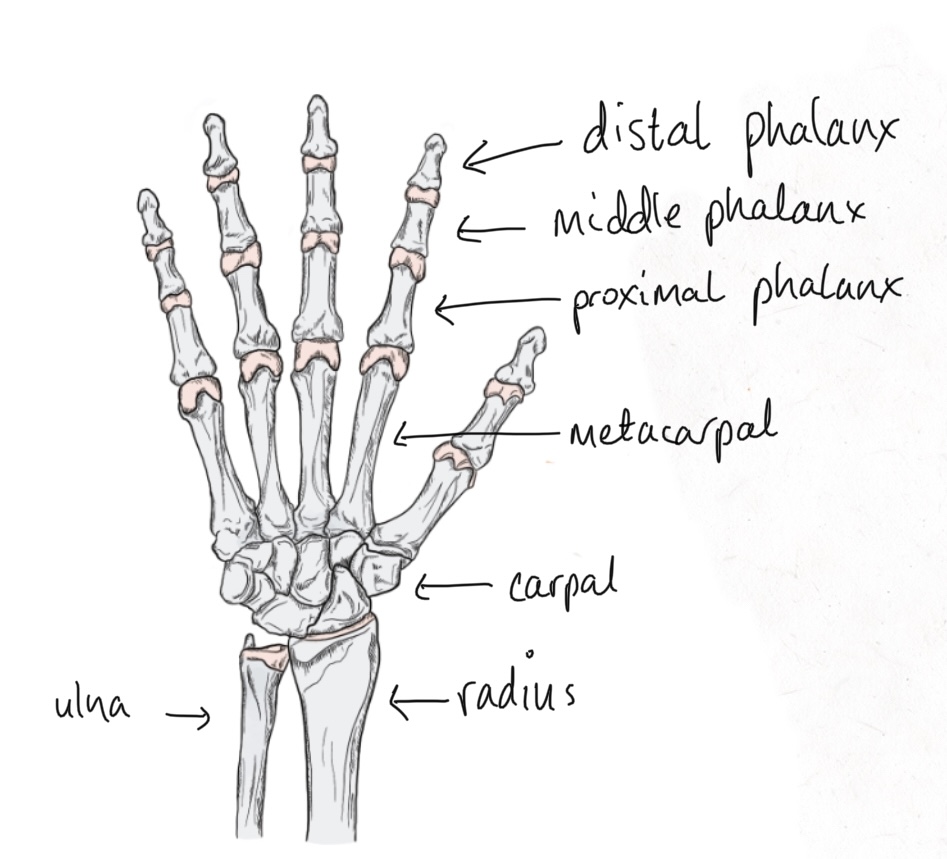

Figure 2 shows the joints of the hand.

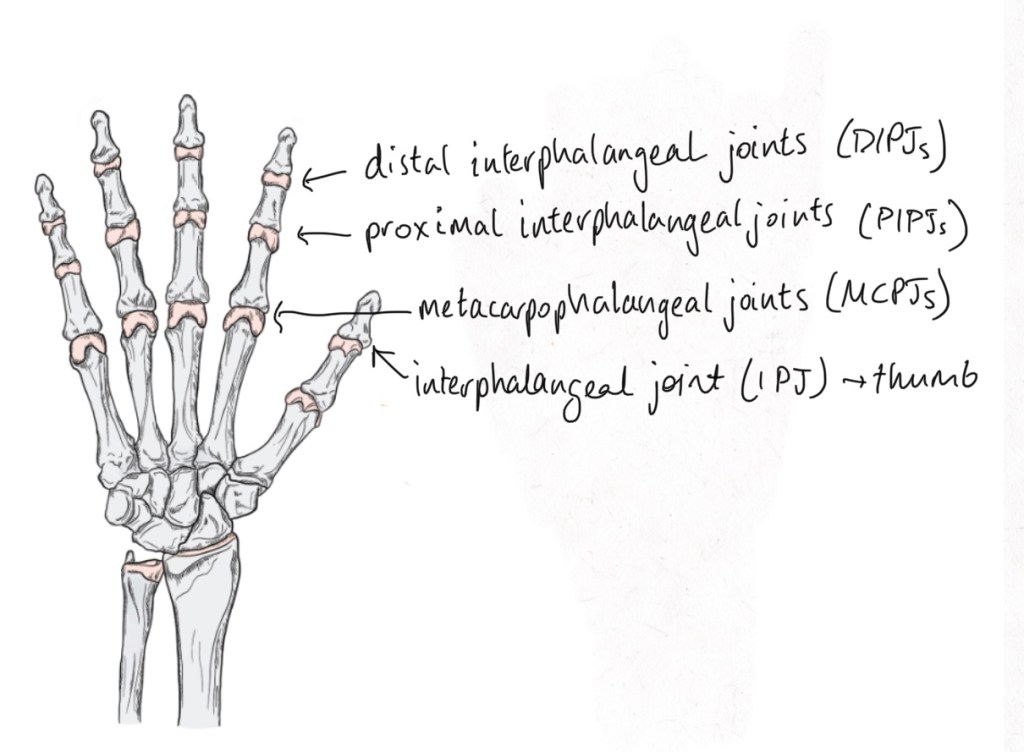

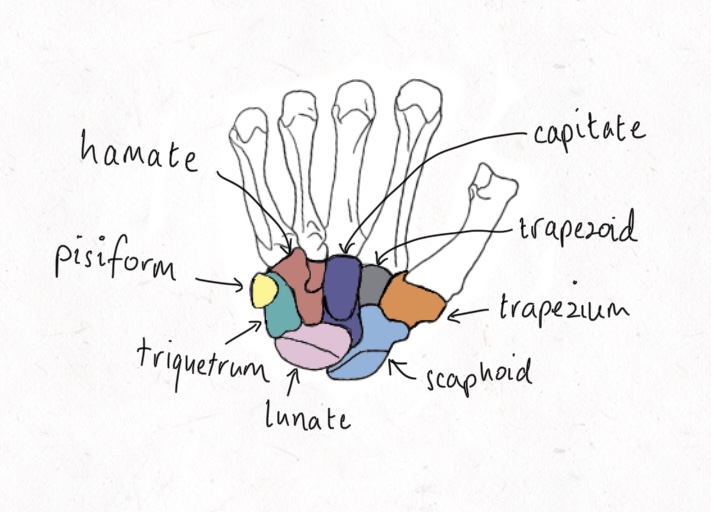

Figure 3 shows the bones of the wrist: the scaphoid, lunate, triquetrum, pisiform, hamate, capitate, trapezoid and trapezium. A useful mnemonic to remember them is “so long to pinky here comes the thumb”.

The median nerve

The main 3 nerves that supply your upper limb are the radial, ulna and median nerves. They start as spinal nerves C5, C6, C7, C8 and T1 and travel to the brachial plexus where they form a network. From the network emerge many nerves, but notably the radial, ulna and median nerves which take their own paths down your arm and forearm to your hand, where they supply your sensation (sensory nerves) and muscles (motor nerves). Figure 4 shows the paths of the median, ulna and radial nerves after they exit the brachial plexus.

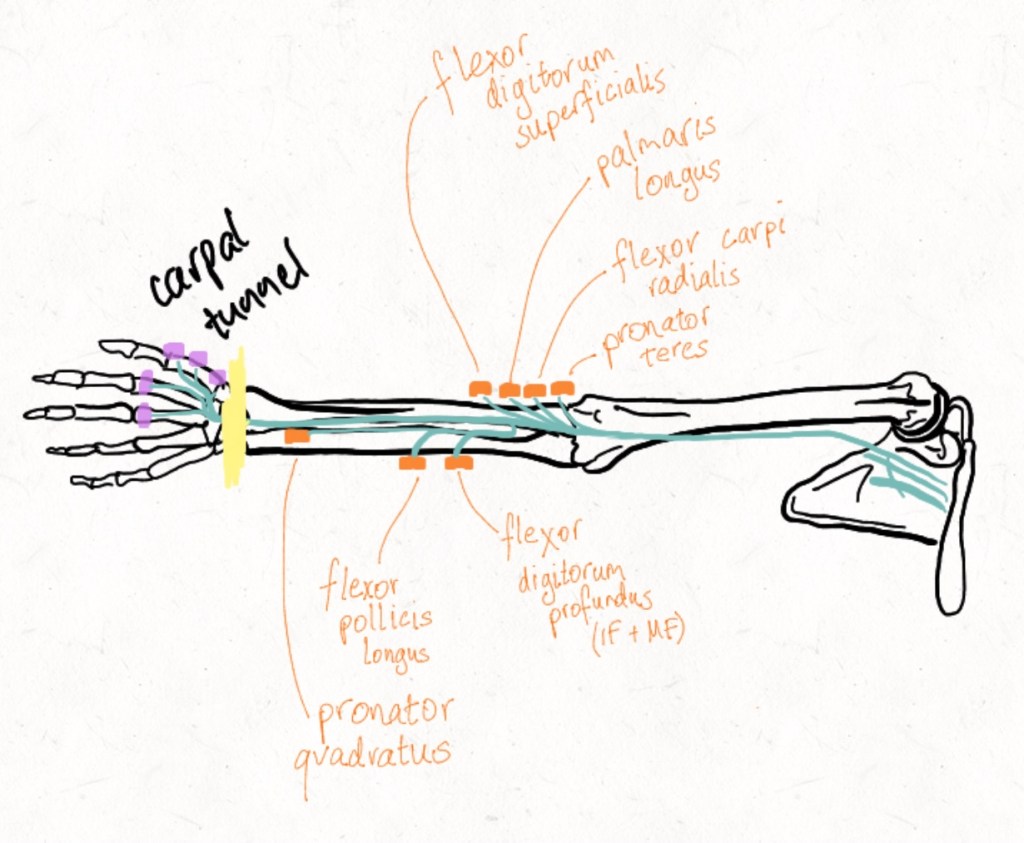

The median nerve has both a sensory and a motor supply. The motor supply of the median nerve before it reaches the carpal tunnel is shown in Figure 5.

The primary actions of these muscles are as follows: pronator teres pronates the forearm. Flexor carpi radialis is mainly a wrist flexor. Palmaris longus is an accessory muscle that is functionally negligible and is absent in 13% of arms but useful because in the distal forearm it runs just over the top of the median nerve so can be used as a marker to find it. Flexor digitorum superficialis flexes your fingers at the proximal interphalangeal joints.

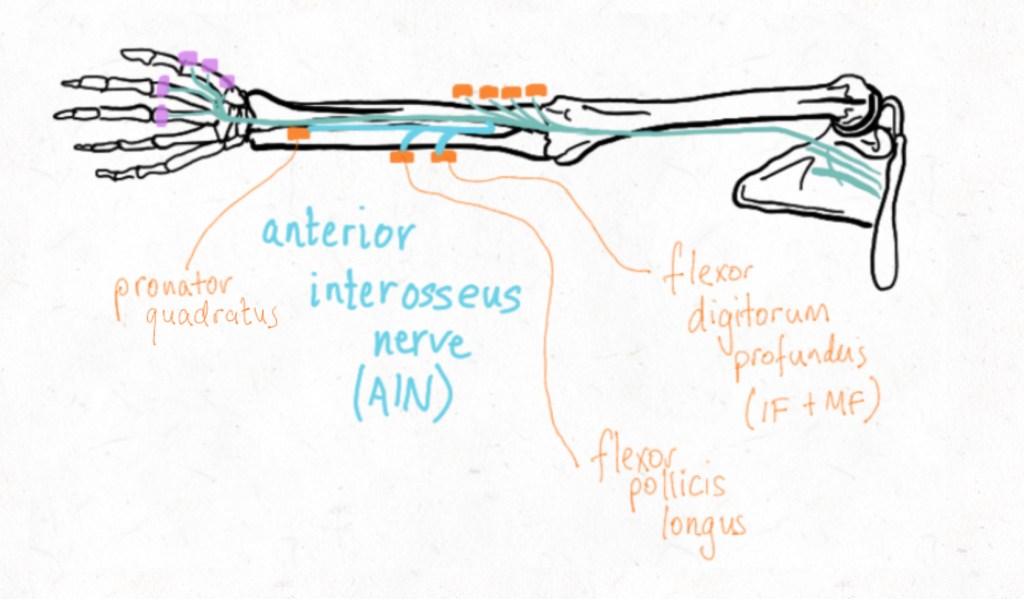

After giving off branches to these 4 muscles, the median nerve has a large branch called the anterior interosseous nerve (AIN) which travels down on the interosseous membrane in between the radius and ulna bones. The AIN supplies flexor digitorum profundus to the index and middle fingers, flexor pollicis longus and pronator quadratus. For a closer look at the AIN, see Figure 6.

Flexor digitorum profundus flexes the distal interphalangeal joints. Flexor pollicis longus flexes the interphalangeal joint of the thumb and pronator teres pronates the forearm.

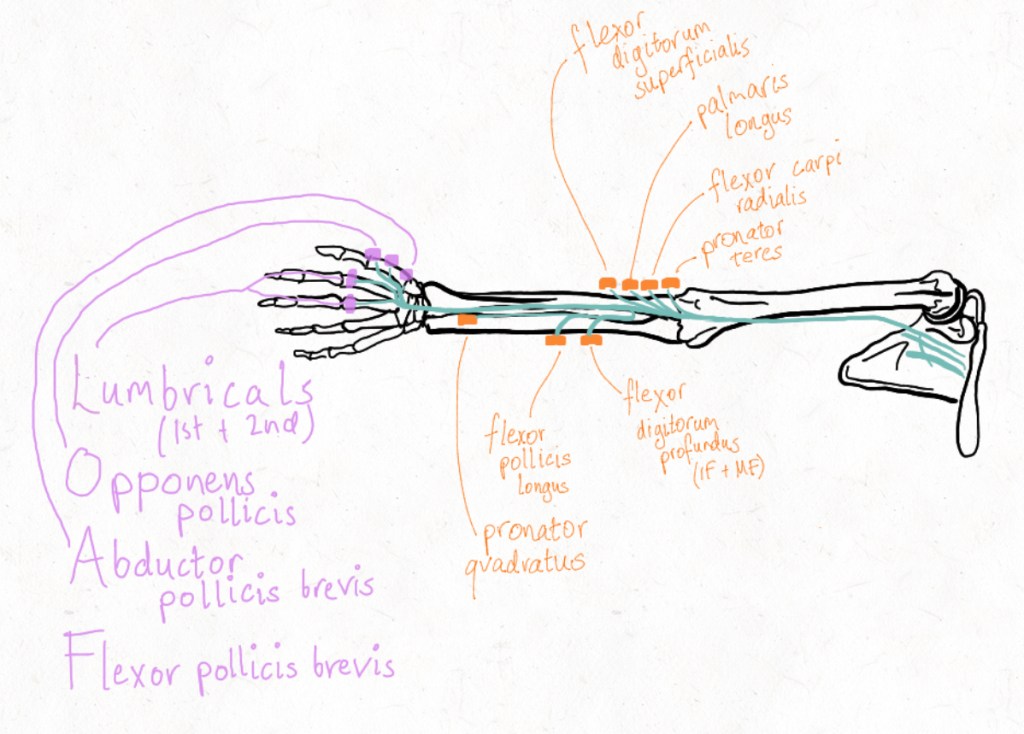

After giving off the AIN, the main trunk of the median nerve travels to the wrist, where it goes through the carpal tunnel. After going through the carpal tunnel, it has a motor branch called the recurrent branch of the median nerve. This branch supplies 4 muscles in the hand, which can be remembered by the mnemonic “LOAF”: the 1st and 2nd Lumbricals, Opponens pollicis, Abductor pollicis brevis and Flexor pollicis brevis (superficial head only). The remainder of the intrinsic muscles of the hand are supplied by the ulna nerve. The motor supply of the median nerve is summarised in Figure 7.

The 1st and 2nd lumbricals help to flex the metacarpophalangeal joints and extend the interphalangeal joints mainly of the index and middle fingers, however a couple of other muscles also help with this action. Opponens pollicis helps to oppose the thumb, which is bringing it over towards the little finger. Abductor pollicis brevis helps to abduct the thumb which is lifting it up to the sky if the patient’s hand is laid flat, palm up, on a table. Flexor pollicis brevis helps to flex the thumb. Combined, the easiest way to test the median nerve motor function is intact after the wrist, is resisted abduction due to the combined functions of intrinsic muscles of the hand.

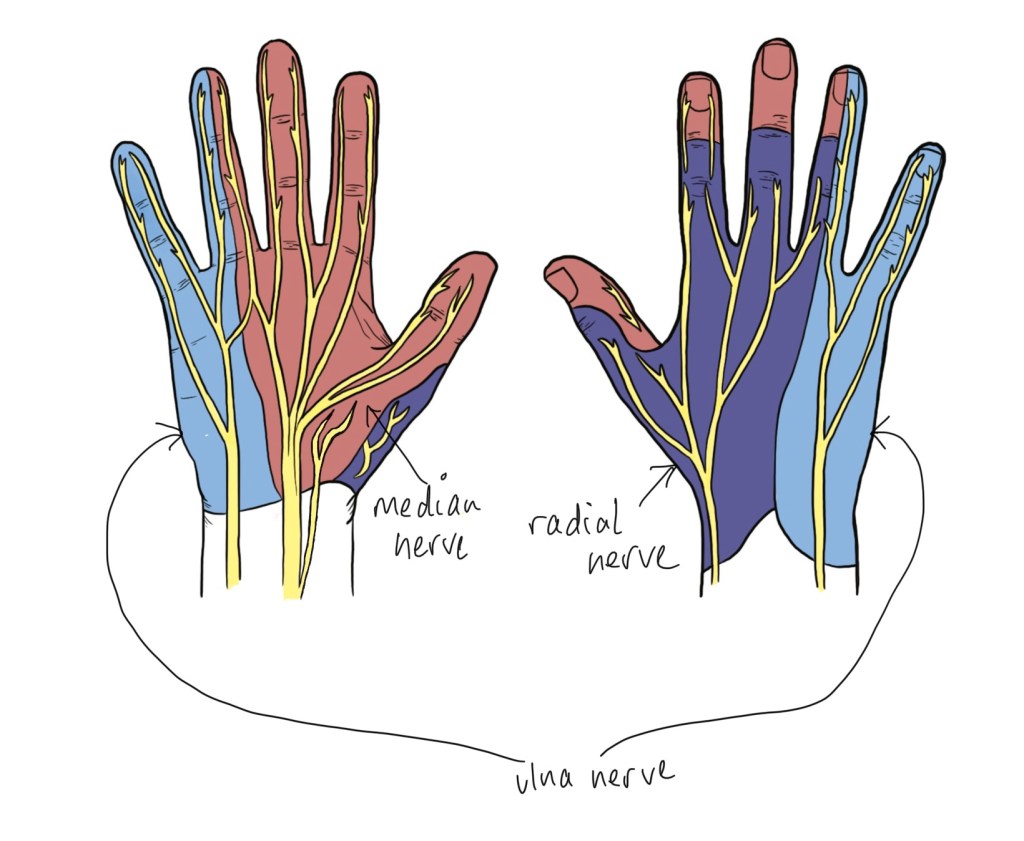

The sensory supply of the hand is outlined in Figure 8.

The median nerve supplies sensation of the palmar aspect of the hand for the thumb, index finger, middle finger and half of the ring finger. The ulna nerve supplies the palmar and dorsal aspect of the hand for the little finger and the other half of the ring finger. The radial nerve supplies mainly the dorsum of the hand over the thumb, index finger, middle finger and half of the ring finger but it doesn’t include the finger tips. An important thing to note about the median nerve is that is has this little branch coming off it before it goes into the carpal tunnel, called the palmar cutaneous branch of the median nerve. This nerve supplies the skin over the thenar eminence and is NOT involved in carpal tunnel syndrome as it passes over or ‘superficial’ to the carpal tunnel.

The carpal tunnel

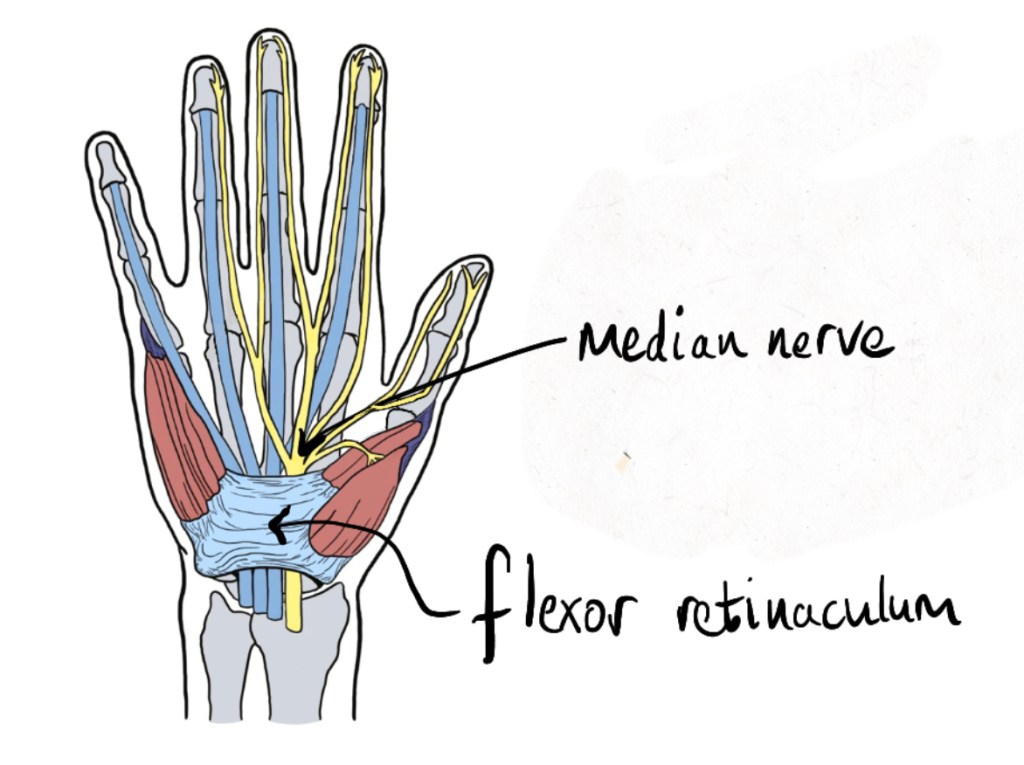

The carpal tunnel refers to a tunnel in the wrist – it has a roof and floor. Let’s talk about what makes up the tunnel itself. The floor of the carpal tunnel is made up of the carpal bones. The roof of the carpal tunnel is made up of the flexor retinaculum (also known as the transverse retinacular ligament), which is a strong band that is attached to the scaphoid and trapezium on the radial side of the hand, and to the pisiform and the hook of the hamate on the ulnar side of the hand. Figure 9 shows a view of the flexor retinaculum as it covers the median nerve.

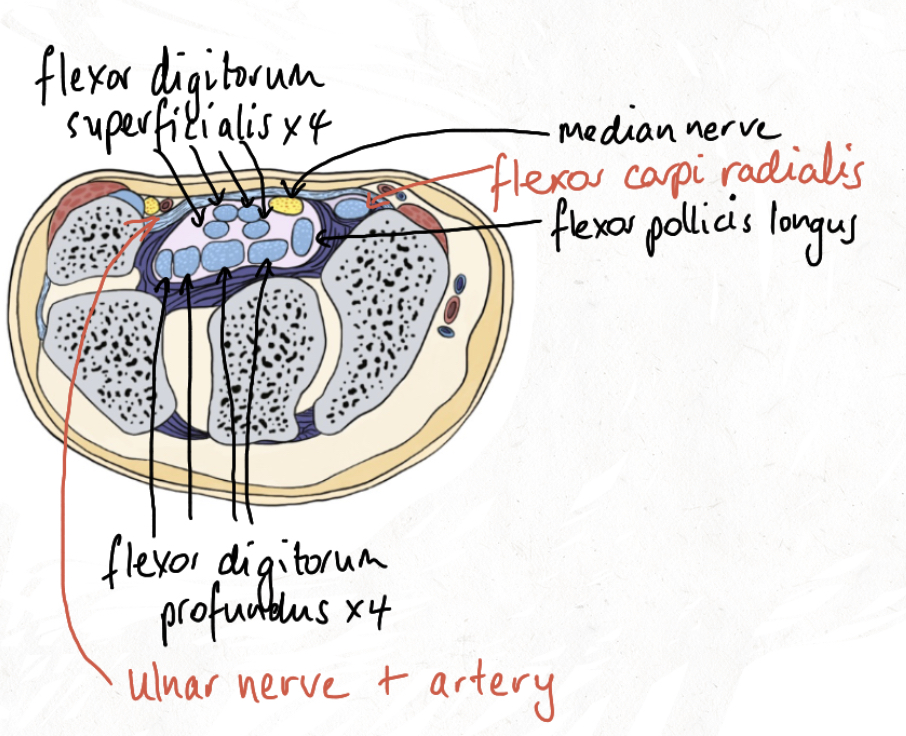

Some of the structures running from the forearm to the hand run in the carpal tunnel and some do not. There are 10 structures that pass through the carpal tunnel: the long flexors of the fingers and thumb and the median nerve. Figure 10 shows a cross section of the carpal tunnel with its contents labelled: the median nerve, flexor pollicis longus, the 4 tendons of flexor digitorum profundus for the index, middle, ring, and little fingers, and the 4 tendons of flexor digitorum superficial for the index, middle, ring and little fingers.

The ulnar nerve and artery can be seen Figure 10 but they travel more superficial to the flexor retinaculum (above it) so aren’t counted as contents of the carpal tunnel. Flexor carpi radialis can also been seen here but it is not travelling in the carpal tunnel.

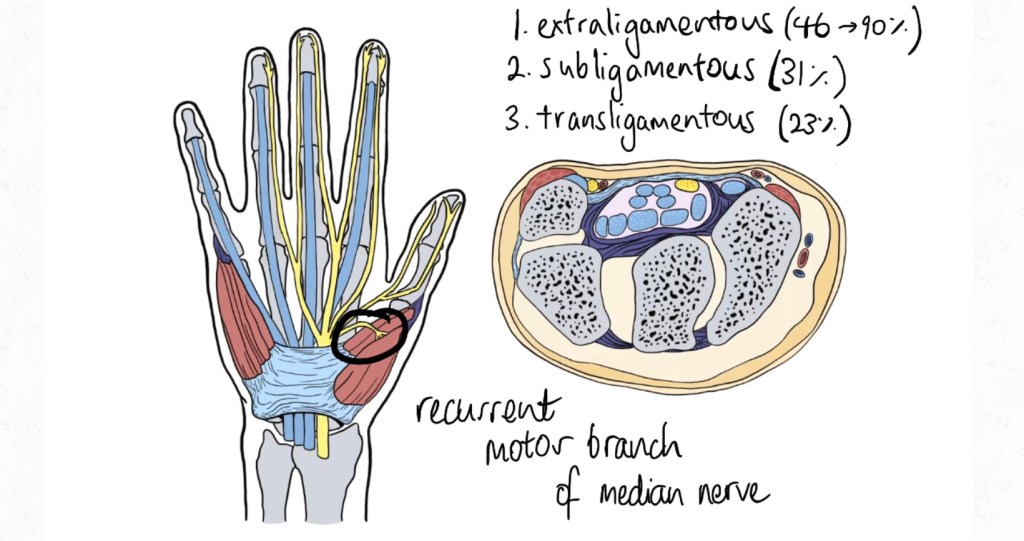

Finally, it’s worth going into a little more detail regarding the recurrent (motor) branch of the median nerve. The recurrent branch of the median nerve can have variable anatomy – this was described by Lanz in 1977. The most common anatomical variation is extraligamentous (46-90%) which means the branch comes off the main trunk of the median nerve distal to the flexor retinaculum (Figure 11). Another variation is subligamentous (31%), which is where the recurrent branch originates underneath the flexor retinaculum. The last variation is transligamentous (23%) which means the recurrent branch pierces the flexor retinaculum to supply the “LOAF” muscles. As you can imagine, it’s important to anticipate variations in anatomy like this so you can avoid injury to this branch. Injury to the recurrent motor branch of the median nerve can mean patients lose the ability to abduct their thumb which can have devastating functional consequences.

Patient Assessment

It’s important to first establish if a patient has carpal tunnel syndrome before you decide whether or not they would benefit from a carpal tunnel release.

Carpal tunnel syndrome is a collection of symptoms and signs caused by compression of the median nerve in the carpal tunnel which affects the function of the nerve. It most commonly occurs in people aged 45-65 and more commonly in women than men. It affects approximately 4% of the population. The most common cause of carpal tunnel syndrome is idiopathic (no known cause). Carpal tunnel syndome is associated with diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, alcohol abuse and pregnancy. There is some evidence that it’s associated with an occupation where the patient is required to work by gripping with their hands. There is no evidence to suggest that carpal tunnel syndrome is associated with typing.

Carpal tunnel syndrome is a clinical diagnosis, meaning you can diagnose and treat carpal tunnel syndrome after history and examination alone. However, often further investigations are sought for more detail or to confirm the diagnosis before the patient is offered management.

If we think back to our anatomy part of the course, we can work out which symptoms and signs you can get compression of the median nerve in the carpal tunnel. Sensation of the hand in the distribution of the median nerve can be altered and the muscles of the hand that the median nerve supplies after it goes through the carpal tunnel might not work as well.

Like all surgical patients, you need to take a full history, examination, investigations and then form a treatment plan. Carpal tunnel syndrome is a clinical diagnosis based on your history and examination but you can subsequently confirm its presences with investigations. There are quite a few different options to treat carpal tunnel syndrome with surgery being one of the last measures – you want to give patients the simple, lowest risk and most effective options first.

History

As will all history taking, it’s best to start with an open ended question. There are specific details that you have to elicit during your history specific for carpal tunnel syndrome; you want to know about any complaints of numbness/pins and needles by the patient, and whether those symptoms are limited to the radial 3 and a half digits. Often for patients with carpal tunnel syndrome, these symptoms are worse at night and they will complain it waking them up at night. Patients may complain of paraesthesias in ‘fixed wrist activities’ such as reading a book or a newspaper, or when they are driving. They also may complain of weakness in their hand or grip, or of dropping things more often lately. You also need to establish whether these symptoms are episodic or persistent – persistent symptoms are confirming for severe median nerve compression and may require a more urgent operative intervention.

Whenever taking a history about issues with the hand, it’s important to know the hand dominance of your patient and their occupation.

Then you proceed with a full history of your patient.

As usual, you need to know details about their past medical history, but particularly you are looking for conditions that are associated with carpal tunnel syndrome such as rheumatoid or osteroarthritis, diabetes, obesity, previous wrist fracture of that hand, or pregnancy.

You also need to ask your patient about their allergies, and their medications – particularly about blood thinners or any immunosuppression which will affect your surgical planning.

Another useful question to ask the patient is regarding any previous treatment or investigations they’ve had to hand ie if they’ve already tried conservative management or if they’ve had a recurrence of their symptoms after a previous carpal tunnel release.

Examination

For a patient presenting with carpal tunnel syndome, it is important to follow these steps for examination: Exposure, Pain, Inspection, Sensation, Move, Special Tests. You want to focus on examining the median nerve but also screen the other nerves of the hand to ensure you’re not missing anything. Always compare the affected hand with the unaffected hand. Ensure you cover the following:

- appropriate exposure – exposed hands to elbows bilaterally, hands on a pillow

- ask about pain – and avoid causing it if possible during your examination

- inspection – scars, muscle wasting particularly of the thenar eminence, ulcers demonstrating damaged skin from a lack of sensation, trophic changes such as degeneration of fat pad, abnormal posturing of the hand

- sensation – test the tip of the index finger for the median nerve, then map out sensation of the median nerve to find where it is and isn’t normal, make sure you check sensation over the thenar eminence for involvement of the palmar cutaneous branch of the median nerve, screen for radial nerve involvement by testing sensation over the dorsal 1st webspace, screen for ulna nerve involvement by testing sensation over the pulp of the little finger.

- move – screening examination of finger movements (resisted extension of digits for radial nerve, resisted flexion of digits for median nerve, resisted abduction and adduction of digits for ulnar nerve), thumb to little finger and test against resistance (opponens pollicis), thumb to roof with dorsum of hand of pillow and test against resistance (abductor pollicis brevis), ‘OK’ sign and test against resistance (flexor pollicis longus and brevis), individually test flexion at distal and proximal interphalangeal joints for flexor digitorum profundus and superficialis respectively, test wrist flexion against resistance (flexor carpi radialis) and forarm pronation (pronator teres/pronator quadratus)

- special tests – there are a number, most common are Tinel’s test (20-50% sensitive, 76-77% specific) where you tap over the flexor retinaculum and test positive if this reproduces the patient’s symptoms and Phalan’s test (68-80% sensitive, 73-83% specific) where you ask the patient to hold their hands in reverse prayer (dorsum of hands touching with fingers pointing to ground) for 60 seconds and test positive if this reproduces the patient’s symptoms, Semmes-Weinstein test (accurate mapping of sensory deficit, can also track recovery), 2 point discrimination

Investigations

The most common investigations are Nerve Conduction Studies (NCS) and Electromyography. This involves the measurement of the speed and amplitude of an electrical current passed along the distribution of a nerve over a specified distance. The advantages of NSC and Electromyography are that they can help differentiate between multiple peripheral nerve disorders, different stages of nerve compression, recurrence of carpal tunnel syndrome and progression of recovery. Disadvantages are that the studies themselves can be uncomfortable and awaiting results may delay appropriate treatment.

Imaging with ultrasound has also been shown to be 82% sensitive and 92% specific. The ultrasonographer studies the median nerve cross sectional area of the compressed part of the nerve compared to the normal part. Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) has been shown to be useful for detecting masses (such as a ganglion within the carpal tunnel causing the patient’s symptoms) but has variable sensitivity and specificity for carpal tunnels syndrome itself.

Management

There are two options for management of carpal tunnel syndrome: conservative (non-operative) and operative. If the patient has not had any treatment yet, you should try conservative first before proceeding to operative management and this may avoid the patient having to undergo and operation.

Conservative/Non operative management options: Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), splinting in neutral, activity modifications, steroid injections.

It’s worth noting that steroid injections into the carpal tunnel can also be diagnostic; if your diagnosis is not clear but the steroid injection supplies relief to the patient, you can be more confident that your patient has carpal tunnel syndrome. It has also been shown that about 1/3 of patients who have a steroid injection to treat their carpal tunnel syndrome require no further surgical intervention.

Operative options: carpal tunnel release.

A carpal tunnel release can be performed as an open or endoscopic procedure. The most common form of carpal tunnel release is an open carpal tunnel release.

Operative Technique

In this topic, we’ll cover how to do an open carpal tunnel release. After your history and examination and perhaps some further investigations, you’ve decided in liaison with your consultant that an open carpal tunnel release is the best treatment for you patient.

Preoperative Planning

Preoperative preparation is the step before the patient’s operation. A carpal tunnel release is an elective operation performed usually as a day case, so you have time to make sure the patient is optimised before their operation. Whilst carpal tunnel releases can be completed under local anaesthetic only, it is common practice at most hospitals in Melbourne for the patient to be treated under local anaesthetic with sedation, or a general anaesthetic. That means you need to be aware of all the usual preoperative conditions: does your patient need to fast? Do they need to withhold any medications like blood thinners or diabetic medications? Have they been told to have someone pick them up from the hospital that day and stay the night with them? Do they need an anaesthetic review or consideration of medical optimisation? All these details are really important to sort in order to reduce the risk of any complications from their operation.

Once the day of the patient’s operation arrives, everything should be already set up for success and most surgeons have a routine they follow to ensure nothing is missed.

First, the patient has to be marked and thier consent checked. It can be useful to draw out your incision at this time with the patient awake, that way you know you can confirm you’ll be operating on the correct side and the patient will know how long they can expect the incision to be.

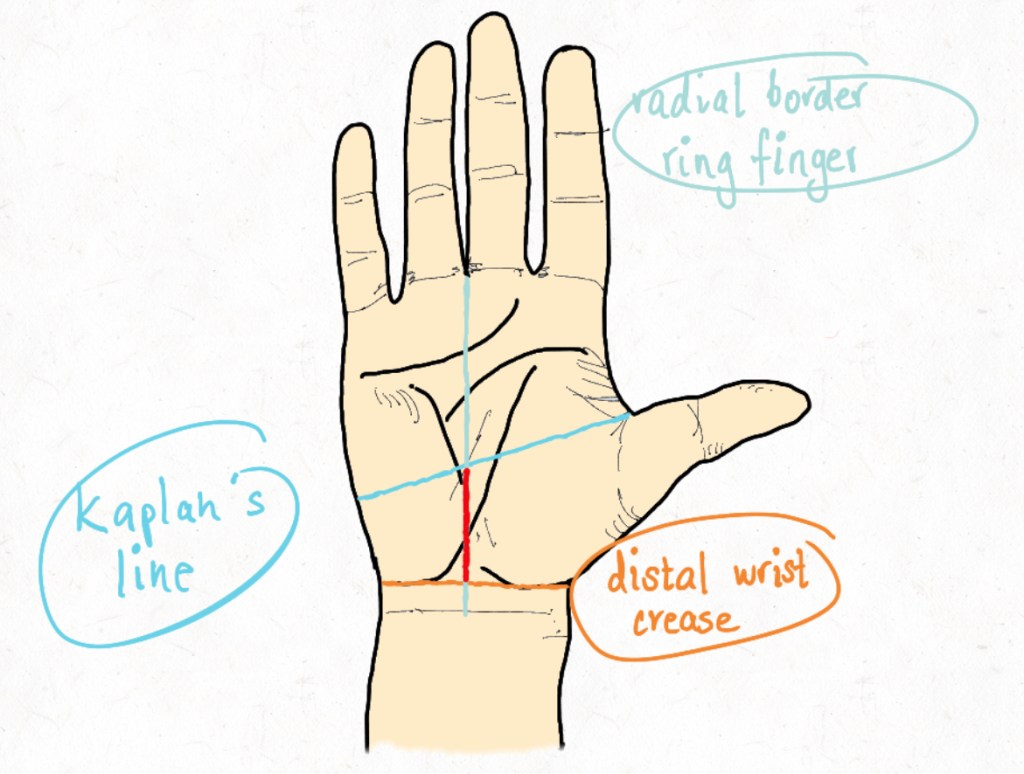

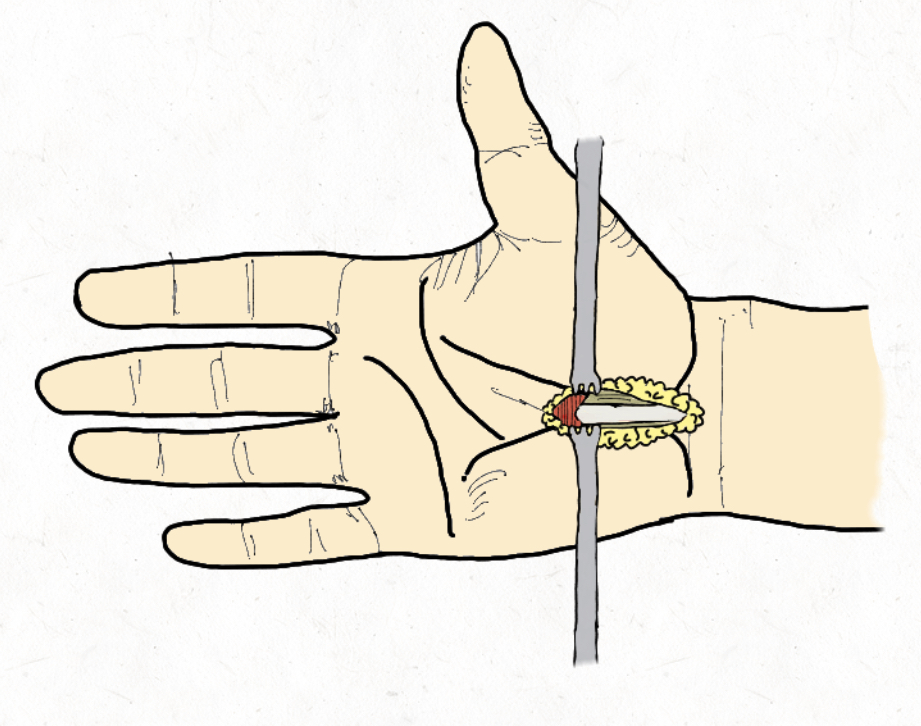

Figure 12 shows the landmarks used to mark your patient for a carpal tunnel release. To mark your incision for an open carpal tunnel release, first you make sure the thumb is abducted, and mark Kaplan’s line following the abducted thumb. You mark the distal wrist crease and then you mark the radial border of the ring finger – usually with the ring finger flexed not extended like it’s shown in Figure 11. You want to make sure you’re marking ulnar to the thenar crease can avoid a scar directly over the palmar cutaneous branch of the median nerve.

Once the patient is in the operating room, usually (but not always), the surgeon requires a tourniquet to be placed on the arm to be operated on to ensure they can operate in a bloodless field. There will be a team time out where the patient and operative details are confirmed, the team introduced and any concerns are articulated. Then the anaesthetist will sedate the patient and usually the surgeon will inject some local anaesthetic into the operative field. An arm table is used.

Once the local anaesthetic is in and the timeout has been completed, the surgeon will scrub. As for most hand surgery, the limb is prepped right from fingertips to elbow and then draped. The arm is then exsanguinated as per surgeon preference and then the tourniquet is inflated. Some surgeons prefer to have a hand-stand or a lead-hand to hold the hand still and keep the fingers extended to help with exposure. Then the surgeon is ready to operate.

First an incision is made in the skin along your marking. Straight away you’ll see some fat bulge out of your incision. If there are any little blood vessels, it’s useful to use bipolar electrocautery to cauterise them as you go and reduce the risk of a postoperative haematoma. It’s also useful to use your assistant throughout this operation to help with your exposure with retractors. If you gently slice along your incision, or dissect with blunt dissectors, you get to some longitudinal fibres – this is the palmar fascia – NOT the flexor retinaculum. It needs to be divided for the length of your skin incision. As you go deeper, you will now see some transverse fibres: the flexor reticulum or transverse retinacular ligament which is the roof of your carpal tunnel.

Make sure you have good exposure at this point, so you don’t miss a transligamentous recurrent motor branch of the median nerve. You need to cut through all the flexor retinaculum without cutting deeper. Once you get through in the central part of your incision, you should be able to see the median nerve at the base of your wound. Take care not to accidentally lacerate the median nerve or any of its branches.

You’ll need to reposition your assistant and their retractors to fully release the distal aspect of the flexor retinaculum. Once you’ve fully released the distal portion of the flexor retinaculum, some fat will bulge out – this is the palmar fat pad and an indication that you’ve released the distal edge of the flexor retinaculum. The superficial palmar arch is within the palmar fat pad so caution is required if further distal dissection is required. Once the distal end is released, you do the same at the proximal end of the wound – this is usually the more challenging end but you must divide the flexor retinaculum under direct vision or risk injury to the median nerve. Careful use of retractors is helpful. Once you are sure you have full release distal and proximal, you ensure haemostasis, either by releasing the tourniquet or by thorough electrocautery and close the incision using interrupted sutures. The wound is then dressed with jelonet (tulle-gras), gauze and a crepe bandage. The tourniquet is released and the patient is roused and wheeled out to recovery. The whole operation usually takes between 5 and 15 minutes.

Postoperative Care

Care of a patient doesn’t end when the operation does. After the operation you have to give clear instructions to the patient to ensure they have an uncomplicated recovery.

First of all, usual surgical instructions need to be given regarding anaesthetic recovery as well as a plan for restarting any medications that were ceased.

It is worth noting that the role for post-operative splinting is controversial, but the literature suggests there is no therapeutic benefit.

Recommendations that should be made are as follows:

- The patient should keep their dressing clean and dry

- Simple analgesia is usually all that’s required but they should stay on top of their pain

- The patient can move their hand, but not use their hand for at least 2 weeks. This prevents scarring but reduces the risk of wound dehiscence.

- For the first 2 weeks, the hand should be kept elevated when resting – above the level of the heart – to reduce postoperative swelling.

A plan needs to be made for a postoperative wound and suture removal review usually within 1-2 weeks.

The patient should be warned that speed and extent of recovery is variable. They may experience a gradual decrease in their symptoms and are unlikely to feel immediately feel symptom free due to postoperative swelling and the time needed for the median nerve to repair. Severe nerve compression can take many months to improve. Patients should be advised they will return to a grip strength of 100% within 3 months.

Sometimes patients may have persistent symptoms, or their symptoms recur after a symptom-free period and they may need revisionary surgery. People are more likely to require revisionary surgery if they are male, smokers, have rheumatoid arthritis, have had an endoscopic carpal tunnel release or have had bilateral carpal tunnel releases simultaneously. Revisionary carpal tunnel surgery is more difficult due to scarring present – the median nerve can be adherent to the scar – and outcomes are generally worse than primary carpal tunnel releases.

Linked Knowledge

Now that you have a good understanding of open carpal tunnel releases, it’s worth mentioning that you have a head start on knowing about a few other things as well. In this final topic, we’ll be coving endoscopic carpal tunnel releases, talking about other median nerve compression syndromes and touching on cubital tunnel releases too.

Endoscopic Carpal Tunnel Releases

So far, we’ve covered exclusively open carpal tunnel releases, which is the most common form of a carpal tunnel release, but you can also do a carpal tunnel release endoscopically. This involves making one or two smaller incisions and passing a camera into the carpal tunnel to divide the flexor retinaculum from the inside.

Benefits of an endoscopic carpal tunnel release are that they use smaller incisions, which reduces the length of the scars and post operative pain for a patient. Disadvantages are that there is an increased risk of injury to the median nerve with an endoscopic release compared to an open release, but complication rates are debated. There are no differences for grip or pinch strength, time to return to usual activities, overall complication rates or operative time. Whether the surgeon does an endoscopic release or an open release remains a matter of surgeon preference, however since the tools and training for an endoscopic release aren’t readily available, open carpal tunnel releases remain the most common procedure.

Pronator Teres Syndrome

It’s worth mentioning that there are many places you can get compression of the median nerve, and whilst the carpal tunnel is the most common place, it isn’t the only place. Another common syndrome of median nerve compression is pronator teres syndrome, which is a compression neuropathy of the median nerve near the elbow. It’s important to keep this in mind when you’re assessing your patient as releasing the flexor retinaculum won’t help their symptoms at all if the problem is more proximal in their forearm! Sometimes in your history, a patient may complain of aching over their proximal forearm, and in your examination you might find involvement of the palmar cutaneous branch of the median nerve. You should also have a high index of suspicion that pronator teres syndrome could be present if there is a lack of the characteristic nocturnal symptoms found in carpal tunnel syndrome. Pronator syndrome is rarely identified on NCS so you have to rely on your history and examination to indicate your patient needs a pronator teres release instead of, or as well as a carpal tunnel release. There are usually vague or absent motor symptoms in pronator teres syndrome.

AIN Syndrome

You can also get AIN syndrome which is a compressive neuropathy of the AIN in the forearm. If this is the patient’s main problem then they won’t have any sensory deficits, because the AIN doesn’t have any sensory supply. The AIN comes off 6cm distal to the medial epicondyle and supplies the flexor pollicis longus, pronator quadratus and flexor digitorum profundus of the index and middle fingers. Thus, it makes sense that on examination, they will have a weakness in grip and pinch – they won’t be able to make the ‘OK’ sign. There are a few places the AIN can be compressed but the most common is by the deep head of pronator teres.

AIN and pronator teres syndromes are both from compression by pronator teres, usually however there is an abnormal NCS with AIN syndrome. AIN syndrome often resolves without surgical intervention and is thought to be caused by a neuritis, prolonged observation is however necessary.

Cubital Tunnel Syndrome

The median nerve isn’t the only nerve that can have a compression neuropathy.

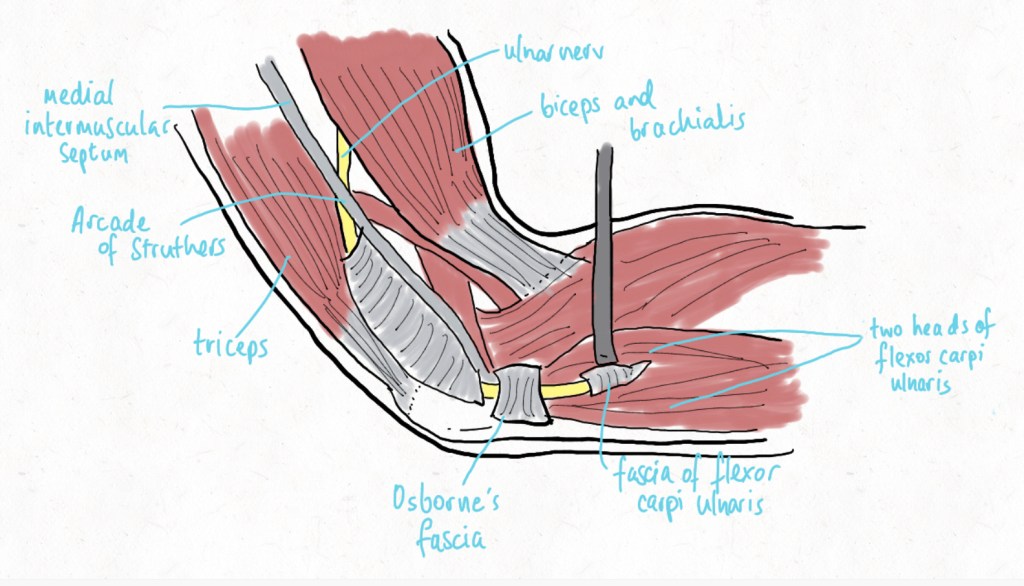

The second most common compression neuropathy of the upper limb is cubital tunnel syndrome, which is due to compression of the ulna nerve at the elbow, most commonly between the two heads of flexor carpi ulnaris (see Figure 14).

The cubital tunnel’s floor is formed by the medial collateral ligament of the elbow and elbow joint capsule. The walls are formed by the medial epicondyle and olecranon and the roof is formed by FCU fascia and Osborne’s ligament (which travels from the medial epicondyle to the olecranon). Patients with cubital tunnel syndrome will have both motor and sensory deficits in keeping with ulna nerve supply and similarly to carpal tunnel syndrome. It is diagnosed by clinical assessment and a similar choice of investigations to carpal tunnel syndrome. Cubital tunnel syndrome is treated first with conservative measures such as lifestyle modifications, splinting or steroid injections and if these are unsuccessful then with a cubital tunnel release which is an operation where the roof of the cubital tunnel is divided.

Reading completion

Thank you for reading. Please click HERE to return to your survey and complete your post-learning intervention quiz. Please close this window after proceeding to ensure you don’t look at this resource again prior to commencing the next quiz. Remember to open your quiz in the same web browser you used for the first half of the study.

References

D’Arcy CA, McGee S. The rational clinical examination: Does this patient have carpal tunnel syndrome? JAMA 2000;283:3110–3117

Deniz FE, Oksüz E, Sarikaya B et al. Comparison of the diagnostic utility of electromyography, ultrasonography, computed tomography, and magnetic resonance imaging in idiopathic carpal tunnel syndrome determined by clinical findings. Neurosurgery 2012;70:610–616.

Dong Q, Jacobson JA, Jamadar DA et al. Entrapment neuropathies in the upper and lower limbs: anatomy and MRI features. Radiol Res Pract. 17;2012: 230679.

Durkan JA. A new diagnostic test for carpal tunnel syndrome. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1991;73:535–538

Evers S, Bryan A, Sanders T et al. Corticosteroid Injections for Carpal Tunnel Syndrome: Long-Term Follow-Up in a Population-Based Cohort. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2017;140(2):338-347.

Gellman H, Kan D, Gee V, et al. Analysis of pinch and grip strength after carpal tunnel release. J Hand Surg Am. 1989;14(5):863-864

Geoghegan JM, Clark DI, Bainbridge LC et al. Risk Factors in Carpal Tunnel Syndrome. J Hand Surg Am. 2004;29(4):315-320

Henry SL, Hubbard BA, Concannon MJ. Splinting after Carpal Tunnel Release: Current Practice, Scientific Evidence, and Trends. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008; 133(4):1095-1099

Hentz VR, Lalonde DH. Self- assessment and performance in practice. The carpal tunnel. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;121(Suppl):1–10.

Jones NF, Ahn HC, Eo S. Revision surgery for persistent and recurrent carpal tunnel syndrome and for failed carpal tunnel release. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;129:683-692

Lalonde DH. Evidence-based medicine: Carpal tunnel syndrome. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2014;133:1234–1240.

Lane LB, Starecki M, Olson A et al. Carpal tunnel syndrome diagnosis and treatment: A survey of members of the American Society For Surgery of the Hand. J Hand Surg Am. 2014;39:2181–2187

Lanz, U. 1997. Anatomical variations of the median nerve in the carpal tunnel. J Hand Surg. 2(1):44-53.

Lawrence RC, Felson DT, Helmick CG, et al.; National Arthritis Data Workgroup. Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and other rheumatic conditions in the United States: Part II. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:26–35.

Liu F, Watson HK, Carlson L, et al. Use of Quantitative Abductor Pollicis Brevis Strength Testing in Patients with Carpal Tunnel Syndrome. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007; 119(4): 1277-1283

Marx RG, Hudak PL, Bombardier C, et al. The reliability of physical examination for carpal tunnel syndrome. J Hand Surg Br. 1998;23:499–502.

McMinn RMH. Last’s Regional and Applied Anatomy. 9th Edition. Elsevier 1998, 2009 reprint.

O’Connor D, Marshall S, Massy-Westropp N. Non-surgical treatment (other than steroid injection) for carpal tunnel syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;1:CD003219

Rodner CM, Tinsley BA, O’Malley MP. Pronator syndrome and anterior interosseous nerve syndrome. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2013 May;21(5):268-75.

Schmelzer RE, Rocca GJ, Caplin DA. Endoscopic Carpal Tunnel Release: A Review of 753 Cases in 486 Patients. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006; 117(1): 177-185

Shores JT, Lee WP. An evidence-based approach to carpel tunnel syndrome. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;126:2196–2204

Thoma A, Veltri K, Haines T et al. A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials comparing endoscopic and open carpal tunnel decompression. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;114:1137–1146.

Tung TH, Mackinnon SE. Secondary carpal tunnel surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;107:1830-184

Tutz N, Gohritz A, van Schoonhoven J, et al. Revision surgery after carpal tunnel release-Analysis of the pathology in 200 cases during a 2-year period. J Hand Surg Br. 2006;31:68-71

Westenberg R, Oflazoglu K, de Planque C, et al. Revision Carpal Tunnel Release: Risk Factors and Rate of Secondary Surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2020;145(5):1204-1214.

Zuo D, Zhou Z, Wang H, et al. Endoscopic versus open carpal tunnel release for idiopathic carpal tunnel syndrome: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Orthop Surg Res. 2015;10:12